On August 28, 2022, KID’s seminal visual novel Ever17: The Out of Infinity turns 20. To celebrate this milestone, I decided to analyze and/or ramble about why, two decades later, its plot still manages to surprise.

WARNING: This article contains massive spoilers for Ever17.

One of the most powerful tools in fiction is tricking your audience. While all mysteries and twists in fiction rely on hiding information from the audience, there is an art to hiding it only from the audience, and not the characters within the narrative, through the structure of the work itself. This draws the audience in, making them part of the narrative, instead of merely an observer, in a way not possible otherwise in traditional media such as a novel or a film. How then, can interactive media such as a video game pull off a similar feat, when the very nature of the medium means that the player is already part of the narrative? Ever17: The Out of Infinity, the 2002 visual novel from writer Kōtarō Uchikoshi and studio KID has the answer.

In H.P. Lovecraft’s 1926 short story The Outsider, an unnamed protagonist attempts to solve the many mysteries of his situation. Why does he live a life of seclusion? Why can he not remember his age? Why does he live in an ancient, decaying mansion? As the protagonist attempts in vain to get information from other people, the mystery reaches its climax, and is solved by him simply looking in a mirror. The protagonist, and by extension the audience, learn what everyone else in the story already knew: that he’s not a human, but a disfigured ghoul. All of a sudden, answers to his questions fall into place, and he takes off, accepting his own existence.

Told entirely in the first person, The Outsider manages to trick the reader through the limited information they receive through the medium of text. Their only interface with the world of the story is the protagonist’s inner thoughts. A short story requires no pictures that would spoil his appearance, no audio that would reveal the voice of a ghoul, and requires no points of view other than that of the narrator. The core of this type of twist, coined “The Tomato Surprise” or “The Tomato in the Mirror” by science fiction editor George Scithers, relies on the audience making assumptions to fill in missing information. While The Outsider never explicitly says that the protagonist is human, the audience makes the assumption, as a human protagonist is the norm in most works of fiction. A compelling mystery is born entirely from the audience’s expectations about the structure and contents of the work.

Subversion of expectations requires expectations to exist in the first place. In video games, this often takes the form of tropes associated with typical genres of game. In a platformer, falling off the stage usually results in a game over. In an RPG, a save point and healing item before a wide open space usually means an imminent boss fight. And in a point-and-click adventure game, every item you pick up will be required for at least one puzzle. In August 2001, when Kōtarō Uchikoshi started writing the outline for what would become his first true mystery game, Ever 17: The Out of Infinity, he chose a genre he was already quite familiar with: the visual novel. Or more specifically, the dating sim.

(Tokimeki Memorial)

While the history of the dating sim (or bishōjo game, as it is known in Japanese) can be traced all the way back to 1982 with Koei’s Night Life, most point to 1994’s Tokimeki Memorial from Konami as the genesis of most of the aspects that make up the genre. Dating sims, a form of visual novel, are often stories of romance, told in the first person, presented via text boxes at the bottom of the screen showing the interactions between the player-insert character, offscreen “behind the camera” so to speak, and the various characters they interact with, typically attractive young women. Typically, the primary gameplay revolves around unlocking “routes”, or branches in the story, based on selecting choices at key moments. These “routes” allow the story to head in different directions, sometimes quite dramatically, from a single starting point. Often, each potential romantic partner will get their own route, with a number of “good” and “bad” ends, depending on player decisions.

Having previously written the scenarios for the dating sims Memories Off and Never7: The End of Infinity, Uchikoshi was an experienced writer, and ready to try something new. Ever17 was envisioned as a science fiction adventure first, and dating sim second, a contrast to Never7, which contained only light sci-fi themes, and Memories Off, which contained none. According to Uchikoshi, a key element of Ever17 was the idea of misleading the player, especially those who had played Never7. Ever17 formally entered development in September 2001 with co-writer Takumi Nakazwa at game studio KID, and the game was released on August 29, 2002.

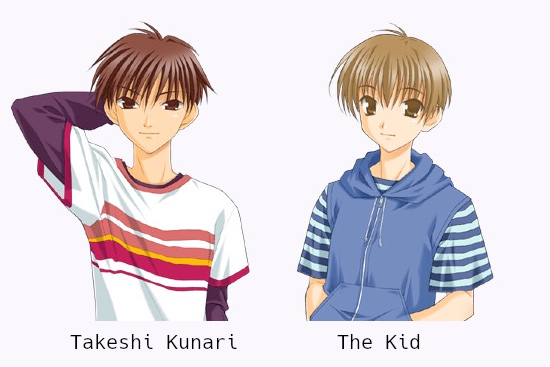

When players booted up Ever17 for the first time, they were met with the appearance of a relatively normal dating sim, albeit one with a unique setting. A brief introduction explains the underwater amusement park of LeMU, and the main characters are introduced: Takeshi, a university student everyman on an outing with some friends, and “The Kid”, a mysterious boy who awakens with total amnesia. An incident occurs, LeMU begins to flood, and amidst the chaos, the player must make their first major decision which will determine who they play as for the remainder of the route.

While both routes initially appear to follow roughly the same plot, just told from the perspectives of two different characters, odd differences start to appear. Why is it that on Takeshi’s route, the seventh person trapped in LeMU is a girl named Coco, whereas in The Kid’s route, it’s a different girl named Sara? Why does the character of You seemingly have two different first names, depending on the route? And why can The Kid sometimes notice these differences?

As the differences pile up, the two routes begin to vary dramatically. In Takeshi’s route, the party discovers that LeMU is actually a cover for a research facility, and members of the group begin to express symptoms of the deadly Tief Blau virus. They make contact with the surface and a rescue pod is sent down, but Coco has seemingly vanished and gets left behind to die. The batteries in the rescue pod begin to die, and Takeshi ejects himself into the ocean as ballast and is killed by the water pressure. The route ends on a somber note for those who have died.

In The Kid’s route, instead of contact being made with the surface, the party figures out how to manipulate the controls to LeMU to make it to the surface themselves. All the while, The Kid is remembering things he shouldn’t, and seeing what appears to be the ghost of Coco, who should not even be in his route. The party manages to escape, but questions remain as the credits roll and the game reveals that somehow, there is still one lifeform aboard LeMU, and that the player has unlocked the one, final “last chapter”, whatever that may be.

The concept of a “true ending” is common in the world of dating sims and visual novels, often serving as a sort of thematic conclusion to the story as a whole, picking and choosing elements from all the other routes. At first, this “last chapter” of Ever17 appears no different, and is entered similarly to the “true ending” of many other visual novels. The player restarts the game (again), starts one of the pre-existing routes, in this case The Kid’s, and waits for a short finale that can serve as the canonical series of events. That is not what Ever17 gives them.

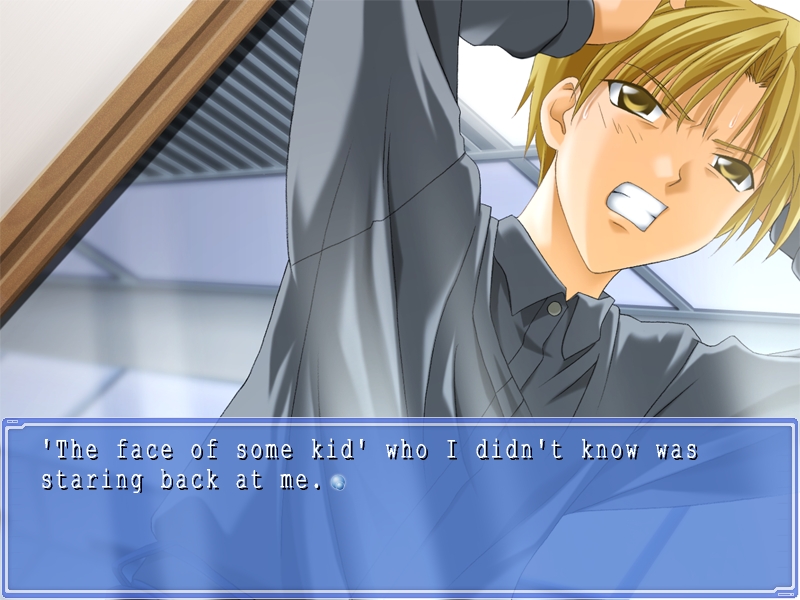

The “last chapter” starts nearly identically to the Kid’s route, barring a few slight changes in dialogue, and proceeds as normal for the first two in-game days of the plot. However, on day three, The Kid does something he did not do last time. He looks in a mirror. And screams.

I DON’T KNOW YOU!

The face staring back is not The Kid the player has interacted with over the last dozen or more hours. The face is a stranger to both the player and The Kid himself, but how? As The Kid passes out, the screen goes black, and the player is left to ponder what, exactly, just happened.

The Kid was the tomato in the mirror. Just like in The Outsider, the audience is tricked by a limitation of the medium. Visual Novels are still told in the first person, which the protagonist invisible, no matter how many routes or perspectives the audience thinks there are. While Takeshi’s route contains a character named “The Kid”, the game never once says that it is the same “Kid” from the route where you play as “The Kid”. The same logic applies to the appearance of “Takeshi” in both routes.

Before they can collect their thoughts, the game immediately throws another curveball the player’s way. When they awake, they are no longer playing as The Kid (or whoever that boy was), but instead Takeshi. For the first time since the prologue, the game has switched perspectives mid-route. Everything the player thought they knew about the structure of the game is starting to unravel. Takeshi’s plot continues as it always has, but clearly something is wrong. The game continues to rapidly switch back and forth as bits and pieces of information are thrown at the player, culminating in a twist that shatters what few expectations the player may still have left: the story never branched, but is in fact, a single, linear timeline.

In 2017, the LeMU amusement park floods with seven passengers aboard. While a rescue pod is eventually sent, only five are saved, as Coco has vanished, and Takeshi sacrifices himself.

17 years later, it happens again with what appears to be an almost identical group of people.

Yet again, Ever17 has used the structure of its medium to trick the viewer. In most visual novels and dating sims, even the ones that Uchikoshi had previously worked on, each route is a branch. It may share a starting point with various other routes, but it is otherwise disconnected. What happens in one route cannot affect another, as only one route can exist at a time. For the majority of Ever17, this appears to be the case. The plot branches when the game asks who the player wishes to play as, and the plots, albeit similar, as entirely disconnected from that point on. By instead having the two routes occur linearly, what occurs in Takeshi’s route (2017) can directly impact The Kid’s route (2038).

After dropping two twists that tear apart the very structure of the game, Ever17 pulls one last trick that operates on an even more meta level, and cements it as a landmark in the history of video game writing. The reason why LeMU flooded twice, why two groups of nearly identical people end up trapped inside, and why even why the game has pulled so many tricks thus far is revealed: to trick the player. After the party is rescued in 2017, the surviving members discover the existence of a four-dimensional being who can travel through time and observe their universe through the eyes of specific people at any point in time. This being, who they call “Blick Winkel,” is the player. By repeating the events of 17 years prior, they hope to catch the attention of the player, who they want to go back in time to save Coco and Takeshi using the knowledge they now know. Their plan works, and the player is able to use information they learned in The Kid’s route (2038) to save the two formerly doomed souls, and the game ends as the characters thank the player for helping them save their friends.

When H.P. Lovecraft played a trick on the readers of The Outsider, the twist derived from the preconceptions the audience had about the medium of the short story. Ever17, while also pulling a similar type of twist numerous times, dares to go one step further. When the player is quite literally pulled into the story, it is no longer a twist derived from the players preconceived notions of what a visual novel is, but instead what their concept of storytelling is at all. In a “normal” story, no matter the medium, the audience, and their expected reactions, are not a factor in the narrative. The goal of a work may be to trick the audience, but that is an outcome, not a plot point. Ever17 takes these expectations and shatters them, resulting in an unforgettable experience where the meta-narrative is the narrative.

Ever17 was not the first game to trick the player, and it certainly was not the last. The way the public consumes and analyses media has changed dramatically over the 20 years since the release of Ever17. Awareness of the common tropes and structural elements that make up works of pop culture has grown due to sites like TVTropes. Video games which break the fourth wall or pull the type of structural twists that made Ever17 famous are all the rage, with titles like Undertale, Doki Doki Literature Club, and The Stanley Parable achieving widespread attention and critical acclaim. And yet, Ever17 continues to stands out for just how well it pulls it off.

Credit to this deleted reddit user for the banner image

Credit to Dinklations for the Tokimeki Memorial screenshot.

Credit to VNDb for the character sprites.

Credit to little_firebird at the LPArchive for the Ever17 screenshots.

Leave a Reply